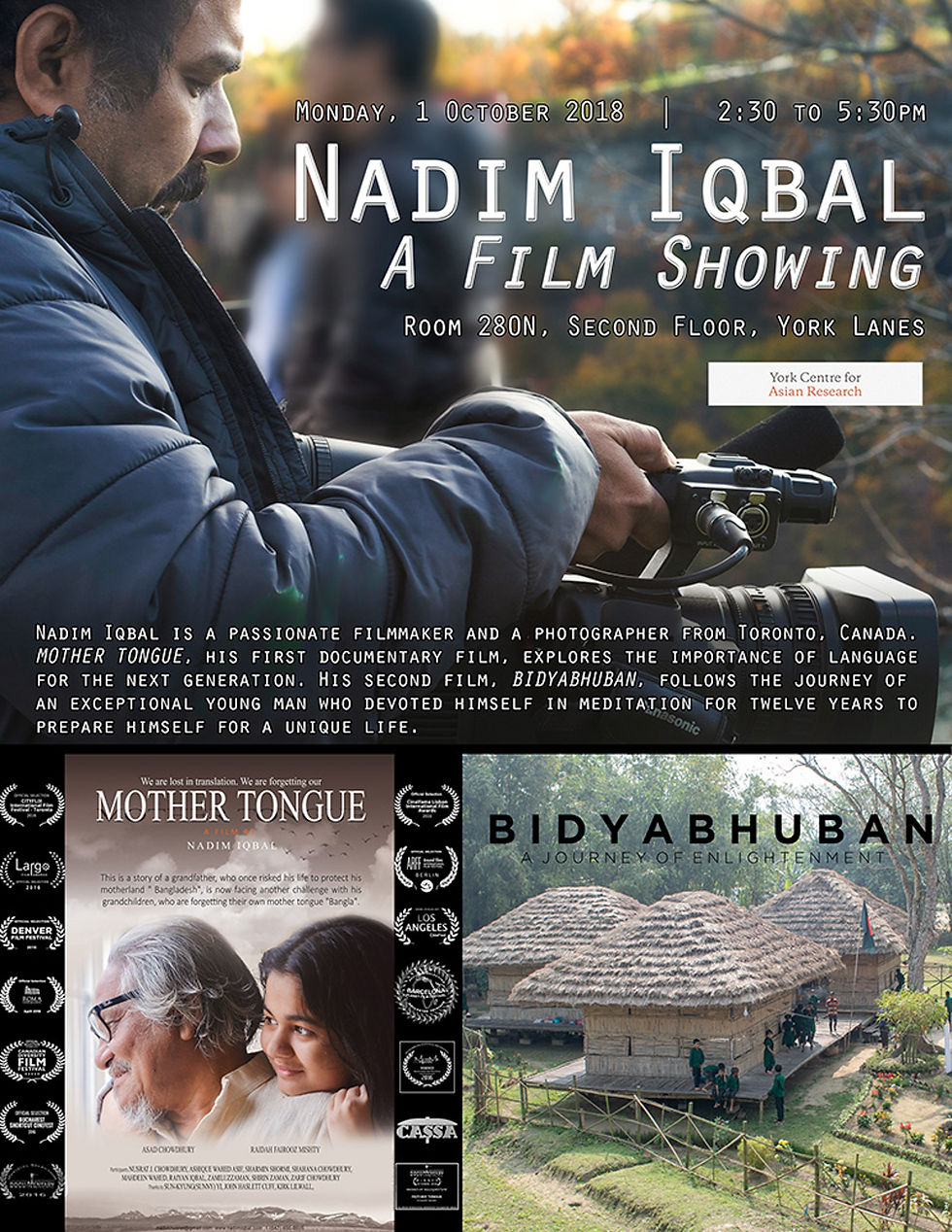

Mother Tongue, 2016

In a typical story of an immigrant family from Bangladesh in Canada, the film brings up the inevitable question of losing one’s mother language and cultural ground rock to English. Nadim takes us into his own family where we meet his adorable teenage daughter and her younger brother. As Canadian children, they speak English which they have learned through school, books, and videos. They play and dance as local kids do in English. Bengali, the language of their parents, and their emotional attachment to it remain on the sidelines. The visit of the grandparents from Dhaka makes the children very happy. The grandfather in the person of Asad Choudhury, a celebrated poet of Bangladesh and freedom fighter has brought books for them written in Bengali which the children cannot read well although the family maintains Bengali traditions and values at home. So, he keeps entertaining them translating into English his poems and interesting anecdotes. Running down the memory lane, he unfolds the history of the noble struggle for mother language in Bangladesh in her earlier identity as East Pakistan and his participation in it as an adolescent student. He goes further into how over time the inherent question of right in the language issue encompassed larger national issues involving economic deprivation and political devilry by the then government, how it eventually brought about a liberated Bangladesh in which he had a part as a freedom fighter. Mishty is enthused, feels proud of her grandfather and their rich Bengali history. She laments her weak Bangla as well as time constraints to read and learn more from Bengali books. Asad notes the absence of a learning process, perhaps institutional, of Bangla with the children which turn out to be a bold comparison when his little grandson keeps reading fluently a French text from school besides his natural fluency in English. He sees the opportunity in learning French besides English as a means of expansion of mind which would help the boy to understand cultures beyond his current geographical boundary. The anguished poet, however, holds that knowledge of Bengali would help these children to know even a wider world, more importantly, their own, ending with the hope that there indeed will be some consistent effort to help the children to learn their mother tongue. In a short span, Nadim has said a lot. His characters are not fictional, and he has presented an immaculate intimate household story. It outgrows its limitation in dealing with the issue in question. It provokes the essential discussion of the relevance of the mother tongue of immigrant families in a host country with a different language and culture. The high emotional attachment to the mother language as seen in the 1952 movement in Bangladesh which claimed a few lives had its mooring in the local culture. Children growing in a host country with different languages and cultures are faced with different realities. Mother Tongue is relegated to the second position as a matter of course. However, they do need to know about their cultural roots and history. This widens the mind and helps develop tolerance, eventually enriching an individual to fit well into the global society. His protagonist in the story seems to tell us so.